More than 20 countries and territories in Europe have launched or plan smartphone apps that seek to break the chain of coronavirus infection by tracking encounters between people and issuing a warning should one of them test positive.

Most countries in the region have opted to use Bluetooth short-range radio to monitor close encounters that could spread the disease, after concluding that tracking people’s movements using location data would be intrusive.

What’s the story so far?

Since there is no cure or vaccine for COVID-19, governments have turned to technology to contribute to broader efforts to contain the pandemic.

After initial efforts misfired, Apple and Alphabet’s Google – whose iOS and Android operating systems run 99 percent of the world’s smartphones – developed a standard that logs contacts securely on devices.

Which countries have launched apps?

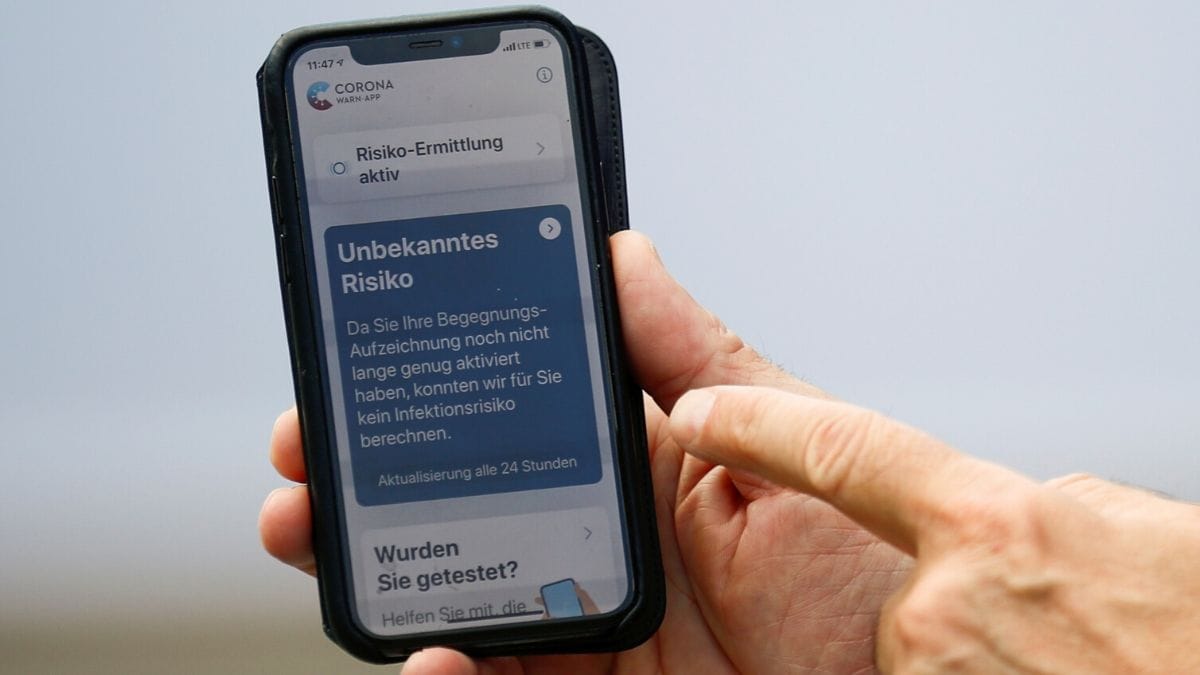

In the EU, Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Latvia, and Poland have launched apps using the Google-Apple standard. Outside the bloc, similar apps are now live in Switzerland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar.

Another nine EU countries plan Google-Apple apps, which would by design be interoperable.

France and Hungary have launched a different type of app that stores information on a central server. The resulting rift in standards means it will be difficult to make all of the apps work seamlessly across Europe.

How do the apps work?

The apps typically show a ‘green’, or safe, status. Should the user spend more than 15 minutes within two metres of another app holder who then tests positive and uploads the result, they would get an exposure notification.

What happens next varies: Germany’s app advises users to seek medical advice; the Swiss shares a hotline number to call; while in Ireland users can opt to sharing their phone number and get a callback from a contact tracer.

Sounds complicated – will they do the job?

The design of Bluetooth-based apps represents a trade-off between usefulness and privacy. It is not possible, for example, to pinpoint the exact time and place of risk events from the app alone.

The most privacy-oriented apps make it impossible for their administrators to monitor the number of exposure notifications going through the system – a key way to measure whether the apps are doing the job for which they are intended.

Yet the Google-Apple framework does allow monitoring of exposure notifications. This is enabled in the Irish app which also has add-ons such as a symptom tracker, where users can volunteer to share information on how they feel, helping the health authorities to map the pandemic.

© Thomson Reuters 2020