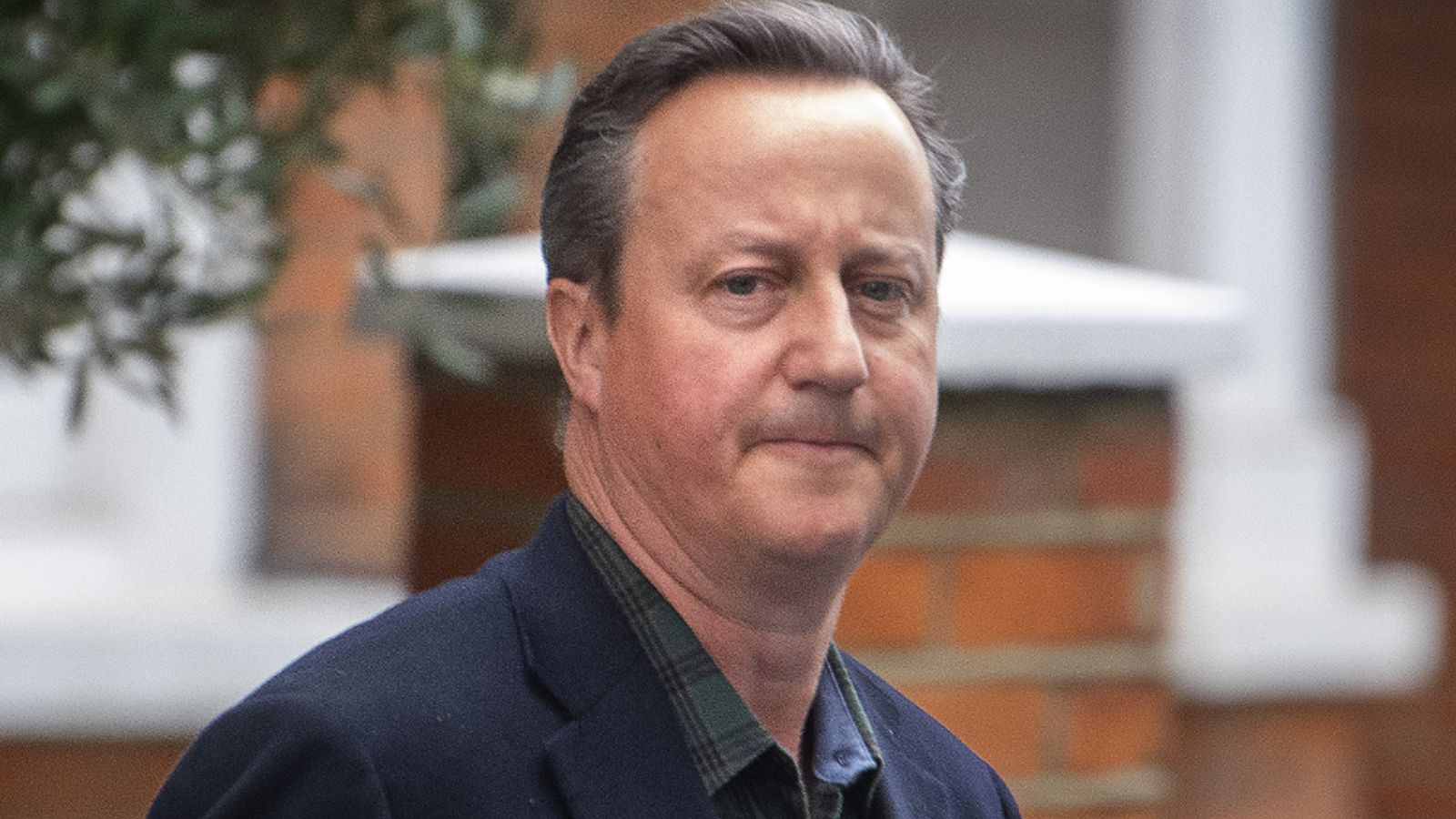

It was always going to be a long and painful afternoon for David Cameron. And it couldn’t have been much worse.

But he didn’t help himself by being evasive, long-winded and giving some answers to questions that will be challenged and disputed.

The overwhelming impression that anyone who sat through nearly four hours of questions by MPs on two House of Commons committees will have formed, was that he was a former prime minister who wanted to cash in and make money.

He looked shifty as he refused several times to reveal how much he was being paid by financier Lex Greensill, leaving Mel Stride, the normally mild-mannered Conservative MP who chairs the Treasury Select Committee, visibly annoyed.

Mr Cameron was forced to admit to Labour’s tenacious Dame Angela Eagle that he enjoyed the perk of free flights to Cornwall, to visit his holiday home, in Mr Greensill’s private jet.

So even though he wouldn’t admit receiving a millionaire’s pay cheque from the Australian tycoon, it was revealed that he lived the millionaire lifestyle of private jets and shares – not share options, he stressed – that the super-rich take for granted.

At one point Mr Cameron spoke of potentially earning the sort of salary a top bank pays to some other former prime ministers. Who could he have meant? Obviously, Tony Blair’s million-dollar salary with JP Morgan.

Listening to Mr Cameron and reading between the lines, while he didn’t mention Mr Blair by name, he gave the impression that he envies the post-Downing Street financial earning power and the status as a global elder statesman of his Labour predecessor.

Heir to Blair? Clearly, you wish, Mr Cameron.

The first hearing of the afternoon, with the Treasury Committee, began badly for Mr Cameron.

He annoyed Mr Stride with his lengthy, self-justifying and long-winded opening statement, which obviously wrecked the committee’s planned timetable.

His statement also included the remarkable claim that “lobbying is a necessary and healthy part of our democratic process”.

Unbelievable. When he was the future once, Mr Cameron condemned “the far-too-cosy relationship between politics and money” and said lobbying was “the next big scandal waiting to happen”.

Predictably, it was the formidable Labour MPs on the Treasury Committee who drew blood.

As well as admitting the private jet perk to Dame Angela, he didn’t deny her claim that if Greensill had succeeded he would have become a multi-millionaire.

But the most brutal Labour onslaught on Mr Cameron came from Rushanara Ali, the Treasury Committee’s smiling assassin, whose style of questioning was unfailingly polite, but her words packed a knock-out punch.

His reputation was “in tatters” and he was “known as Teflon man”, she said.

Mr Greensill was “using and exploiting” him, but the former prime minister “turned a blind eye to things that were blindingly obvious”, she told him.

“Well, obviously, I take a different view,” Mr Cameron said calmly, refusing to be goaded into losing his temper.

It was a calm, disciplined performance throughout, even if it was shifty.

Then, in a dramatic finale to a pulsating hearing, Ms Ali hit back: “You should have known better. You were the future once.”

And Greensill, she said, was “acting like a con artist”.

But while it was Labour MPs spearheading the attacks on Mr Cameron in round one of his battering, it was two old bruisers from the Tory right – knights of the shires Sir Bernard Jenkin and Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown – who led the onslaught in round two, at the Public Accounts Committee.

Subscribe to the All Out Politics podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

The pair, banished to the back benches during the Cameron years, hammered Mr Cameron on the “revolving door” of ex-ministers cashing in and conflict of interest.

Then another Tory right-winger, ex-UKIP leader Craig Mackinlay, came up with some colourful language, denouncing Greensill as an “oddball sort of whizz-bang scheme” and declaring: “I wouldn’t have touched this with a barge pole, personally.”

All afternoon, plenty of questions went unanswered and plenty of answers raised further questions.

For instance, Mr Cameron claimed his contacts with Chancellor Rishi Sunak and Health Secretary Matt Hancock were public knowledge.

Well yes, but only because the Financial Times and The Sunday Times exposed them.

And bizarrely, he blamed “spellchecker” on his phone for a text message in which he appeared to show advance knowledge of an interest rate cut.

In a Commons debate last month, several Labour MPs called Mr Cameron “dodgy Dave”, an insult first used by Dennis Skinner some years back.

The documents released to the Treasury Committee suggested he was more like “desperate Dave”, however. Dame Angela said his actions were more like stalking than lobbying.

But by managing to appear dodgy, desperate and shifty all at the same time, there’s now every chance Mr Cameron will be hauled back before MPs to answer more questions very soon.