It may not have the setting or the showbiz appeal of the coming leaders’ summit in Cornwall.

It may not have quite the same momentous feel as the main summit – Joe Biden’s first as US president, Angela Merkel’s last before potentially standing down as Germany’s chancellor.

But the meeting of G7 finance ministers in London today and tomorrow could in the long run prove even more important through a historical prism.

For not only is the meeting of finance ministers of the group of seven industrialised economies the first face-to-face summit of such ministers since COVID-19 struck, it could be the decisive moment triggering the biggest overhaul of international tax rules in more than a century.

The ministers meeting at Lancaster House in London are unlikely to come to detailed commitments about what to do with business taxation. Such things will have to be hammered out in future meetings of both the G20 – a bigger grouping of nations – and the OECD, a club of developed economies, later on this year.

But if the G7 finance ministers do indeed commit to changing the way we calculate corporation tax and introducing a global minimum rate, it will provide the momentum which could well turn this long-held dream into a reality.

The backstory to how we got here comes down to the way the global tax system has worked since the early decades of the 20th century. Businesses are mostly taxed on the basis of their earnings.

That makes plenty of sense, but it opens the system up to abuse since, in an era where companies bestride the globe and where different jurisdictions compete for the lowest tax rates, it has allowed many companies to shift profits to reduce their tax bills.

There have been countless stories in recent years of major corporations paying disproportionately low levels of tax, since they can shift profits to tax havens and low tax countries.

The OECD has long been attempting to devise rules to prevent these practices.

Its latest scheme calls for two “pillars” to confront the issue. The first is to reform the way taxes are calculated, using sales figures in each country to attempt to calculate a fairer apportionment of tax revenues around the world. The second pillar is to ensure countries stop competing in a race to the bottom on tax rates. That’s where the idea of a global minimum corporate tax rate comes from: if everyone commits not to cut rates below a certain level that makes it far harder for companies to avoid taxes.

However, the OECD has struggled to get support from enough leading economies and in the absence of an international agreement some countries have attempted to impose taxes on tech giants – including Britain’s digital services tax – to try to redress the balance.

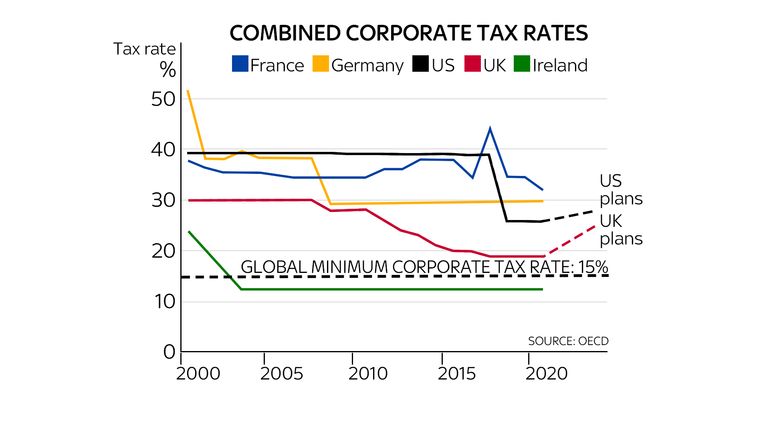

However, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has gone further than any previous incumbent in supporting the OECD process. She has proposed a global minimum tax rate of 21%, though she later reduced that to 15%.

The UK has been somewhat more reluctant, though it says its reluctance is primarily because it is concerned that the US will push ahead with the global minimum rate without addressing pillar one – the need to reshape the calculation of taxes. Treasury sources say that allowing this to happen would advantage US companies at the expense of everyone else.

As this G7 finance ministers’ meeting approached, work has been happening behind the scenes to forge a consensus between the seven countries involved. Sources close to those discussions say it is now quite possible that the meeting will agree in principle to the reforms. However, the degree of detail remains unclear and a last-minute change of mind from one of the nations could scupper these plans.

Given all G7 nations have considerably higher business tax rates than the US proposed level of 15%, they are likely to be less directly opposed to this part of the scheme.

However, in a twist of fate, it turns out the meetings will also be attended by Ireland’s finance minister, Paschal Donohoe, who told Sky News recently that Ireland, whose corporate tax rate is 12.5%, is strongly opposed to the US plans. Mr Donohoe is attending in his guise as president of the Eurogroup, the grouping of eurozone finance ministers. He is thought to have arranged a bilateral meeting with Ms Yellen to discuss the tax reforms.

Given these rules could result in billions of dollars of tax revenue being shifted around the world and that it could help stem some of the tax avoidance big companies carry out, the stakes are very high indeed.