It is a striking number, a historic one. The strongest economic growth since 1941.

The Bank of England’s decision to upgrade its growth forecast for this year from 5% to 7.25% is not exactly a surprise.

Everyone was expecting a big number, and indeed up until the third lockdown over the opening months of 2020 that number was precisely what the Bank was expecting in gross domestic product (GDP) growth this year.

These aren’t the only provisos.

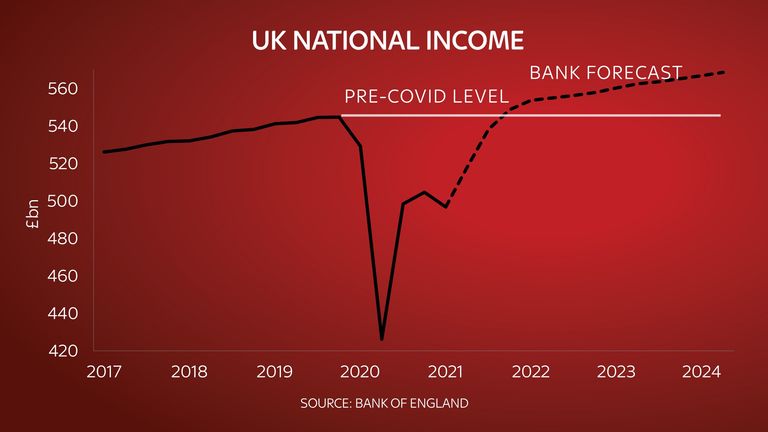

Of course, this is less a boom than a rebound following the extraordinary 9.75% fall in 2020.

We still won’t get back to where the economy was pre-COVID until the end of this year.

But even so. This is a growth rate that hasn’t been experienced in this country in nearly a lifetime.

And the Bank believes that thanks to the lockdown easing slightly sooner than it expected and the success of the vaccination programme, that moment where we regain our pre-COVID level of national income will come some months sooner than previously anticipated.

Perhaps the best comparison for this year of growth is the 7-8% rate in 1927.

That year the economy was also bouncing back from an enforced economic shutdown – though in that case the shutdown was not a pandemic but the 1926 General Strike.

The question now is whether what follows feels like the “roaring ’20s” or something else entirely.

And on that, the Bank is pretty clear.

Look a couple of years on from today and rather than seeing strong growth you see GDP expansion down at a mere 1.25%. This is, frankly, a desultory growth rate.

As the governor, Andrew Bailey, told me, that’s a long way short of the typical growth rates – “trend growth” as it’s sometimes called – only a decade or two ago.

“In [the Monetary Policy Committee’s] early days we always used to think about 2.25% was a UK trend rate of growth and of course it’s been lower than that, since the financial crisis: perhaps between 1.5% and 1.75% – not more than that.”

Now it might be tempting to put this down to some recent, familiar explanations – long-term COVID-19 scarring or Brexit, for instance.

But while there could well be some permanent scarring from COVID – in other words the economy being permanently smaller than it would have been had the virus not struck – the Bank is gradually cutting back its expectation for how big that’ll be.

In its previous forecasts it thought the degree of scarring would be around 1.75%; now it thinks it will be about 1.25%.

As for Brexit, the Bank thinks trade has rebounded somewhat from the falls in January, but not entirely, and it says it is still watching and waiting to see whether there’s further evidence of long-term damage (it already assumes a permanent hit, but that’s now baked into its forecasts).

But in practice, the real explanation for the weak growth rates pencilled in for later in the 2020s is more prosaic and, perhaps, more troubling.

Britain’s long-term productivity rate just seems to be stubbornly lower than it used to be.

It is an old conundrum with all sorts of consequences: less income to be shared among us, less money in the Exchequer, less prosperity in the long run.

And we haven’t got any closer to solving it.