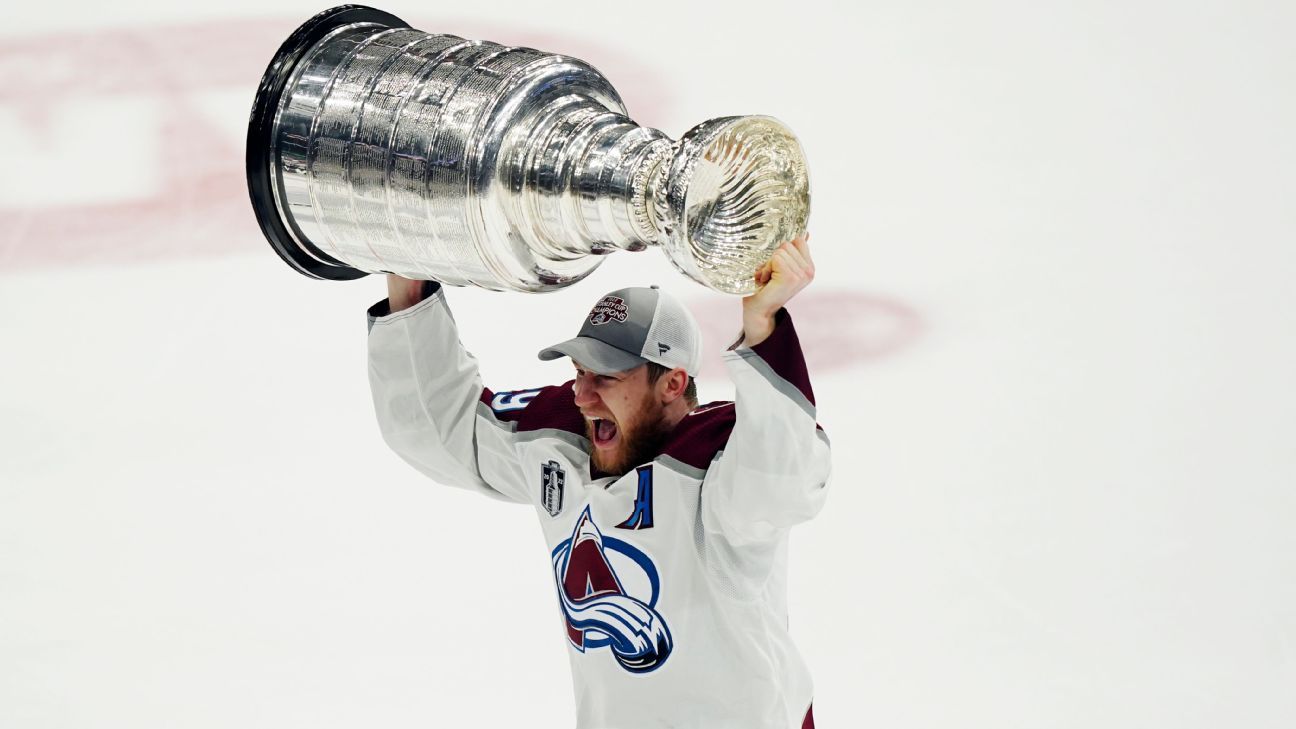

TAMPA, Fla. — Nathan MacKinnon raised the Stanley Cup over his head and then lowered it to his lips.

The Colorado Avalanche, a team he dreamed of playing for as a child, were champions for the first time since 2001. MacKinnon, their 26-year-old superstar, had a goal and an assist in their 2-1 Game 6 win over the Tampa Bay Lightning to earn that championship.

As he raised the Cup again, there was something peculiar about MacKinnon’s face. Something that hadn’t been there at the end of any of his previous playoff series: a beaming grin.

“He doesn’t smile too often. He’s all business. But you could just see how excited he was to lift it,” Colorado general manager Joe Sakic said. “I’m so excited for him. Maybe now he can relax and enjoy the summer a little bit.”

MacKinnon scored 13 goals en route to 24 points in the playoffs, doing all he could to secure a championship for Colorado and lock down his own legacy as an NHL star. Even if the latter didn’t matter much to MacKinnon before the Stanley Cup Final.

“Legacy for who? You guys?” he said on media day. “I’m just having fun day by day. Doing the best I can for my team. That’s all I’m thinking about.”

To begin his own legacy, he ended another, eliminating the back-to-back Stanley Cup champions.

“It’s crazy how they went back-to-back,” MacKinnon said. “I might get fat as s— right now, so I don’t know if we’re going back-to-back. But I’m going to enjoy it for sure.”

The Lightning have said they needed to lose before they could learn to win. So did MacKinnon. Those anguishing disappointments in the regular season and postseason that had come to define his nine-year NHL career were, in the span of one victory, undoubtedly worth it. Those years of demanding nothing short of excellence from teammates to the point of behind-the-scenes rigidity. That personal journey for MacKinnon in which he learned, from mentors such as Sidney Crosby, the mindset to unlock playoff achievement.

It all became worth it, because Nathan MacKinnon could finally relish in the unbridled elation of bringing a Stanley Cup championship to the Avalanche.

On the ice, he has been a star. Off the ice, MacKinnon was “the battery of our team, he makes everything go,” as defenseman Erik Johnson put it. The guy who would say or do anything to ensure that his team finally reached its potential.

“I think what makes him this good is hypercompetitiveness,” said former Avalanche defenseman Ian Cole, now a member of the Carolina Hurricanes. “Even in practice. He’ll do whatever it takes to win. Even if that means calling out his own teammates.”

Which MacKinnon would do, with frequency. In finally earning a twirl with Lord Stanley, one of the best players on the planet had molded himself and his teammates into champions — even if it meant crushing some egos along the way.

WHEN DEFENSEMAN JOSH MANSON was traded by the Anaheim Ducks to the Avalanche ahead of the deadline, he knew about MacKinnon’s intensity as an opponent on the ice. He didn’t know that intensity paled in comparison to what players experienced with MacKinnon away from the games — in practice, in the locker room and in life.

“Well, he is intense. Scary? I guess that depends on the player. But he is very intense,” Manson said. “But that’s why he’s different. He drives everybody else around him to be better, and that is what’s so special. He’s in your face. He says ‘I expect this from you. I’m here to win.'”

Many who played with MacKinnon have seen or experienced first-hand how those expectations manifest. There is yelling. There are blunt critiques and unfiltered advice. There is a standard of excellence applied to everything from a practice drill to a fitness decision.

“For one of the best players in the league, who dedicates so much of himself to the organization, if he’s a little intense when someone doesn’t act the right way? I don’t see that as a problem,” said Pierre-Edouard Bellemare, who played with MacKinnon for two seasons before leaving for the Lightning last summer.

Hurricanes defenseman Cole spent parts of three seasons with the Avalanche and considers MacKinnon a friend.

“I don’t necessarily think that competitiveness is a bad thing. Yes, it is abrasive. But I think that competitiveness and that abrasiveness and ability to just call anyone out at any given time, about anything, whether he’s right or wrong, it makes guys step up to the plate and makes guys play better,” he said. “They’re either scared to be called out or they don’t want to look foolish and they’re stoked to play better.”

That goes for NHL veterans on the Avalanche as well as the newbies.

“A lot of young guys are like, ‘I just don’t want to f— up and get screamed at,'” Cole said.

Cale Makar was one of those young players. He famously joined the Avalanche in the 2020 playoffs, straight from the NCAA. He had six points in 10 playoff games and then won the Calder Trophy as rookie of the year the following regular season. It was obvious he was going to be a special player.

That wasn’t good enough for MacKinnon.

“Cale had all the talent in the world,” Cole said. “But Nate was still pushing him. Telling him it wasn’t good enough. Asking him what he was doing on the ice. Telling him ‘you gotta be better than this’ on the power play or whatever. And now Cale is one of the best players in the NHL. When you surround yourself with people who make you better, then you have to automatically elevate yourself. That’s the culture that Nate was building there.”

That culture is something that Makar has embraced, and the Norris Trophy winner credits MacKinnon for driving him in practices.

“He’s obviously a touchstone, a very intense guy,” Makar said. “And I think, for me, I’m a very competitive guy. So it’s fun, especially practicing with him. He’s a guy that pushes other people to become better, and I’m a guy that likes to think I’m trying to make people around me better as well.”

Logan O’Connor has been that young player, too. This was his first full campaign with the Avalanche after playing parts of the last three seasons with the team.

“He’s a great role model for a lot of young guys. He’s at the peak of his game, in the conversation for one of the best players in the world. He’s always out there before practice and after practice, pushing guys. Someone messes up a rep …”

O’Connor paused.

“You need someone to push everyone. When guys aren’t sharp or they’re sleepy, because it’s a long season, he’s always there to refocus people and keep them accountable,” he continued. “I think that’s the biggest thing with our team. The accountability throughout the lineup. Everyone has high standards for each other and he’s one of the guys who keeps those standards up.”

Even if those standards mean you don’t dare, for example, eat junk food in his presence.

“I’m not a candy guy,” O’Connor said. “Luckily had nothing to do with that.”

CANONICALLY, THE GREATEST example of MacKinnon’s abrasive intensity was provided by former Avalanche defenseman Nikita Zadorov last summer. He did a Russian-language interview in which he shared some of MacKinnon’s dietary standards, which he said were pushed on his teammates.

“Two years ago in Colorado, he got rid of all the pop, ice cream and desserts,” Zadorov said. “He got rid of them from the dressing room and pre-game meals. He even got rid of the white sauce for pasta. He replaced the actual pasta itself with chickpea pasta. He says, ‘Guys, if you want to eat crap, you have the offseason for that. When you come here, there will be none of that because we’re winning the Cup.'”

He then compared MacKinnon’s behind-the-scenes intensity to that of Michael Jordan. Seeing it pop up on social media, MacKinnon reached out.

“I read the first paragraph of it on Instagram and I’m like, ‘I can’t read this.’ Like, he compared me to MJ. I’m like, “Dude, you’re such a donkey,'” MacKinnon said. “I texted him. I’m like, ‘Bro, can you stop talking about me in Russia?'”

MacKinnon didn’t deny that he eats healthy and encourages teammates to do the same.

“Maybe if I saw ‘Z’ eating a big chocolate bar I’d give him crap,” he said. “But I’m not a psycho eater or anything. I like to eat what everyone else does too.”

Makar said that, for the record, MacKinnon would not yell at him if he saw him eating a cupcake.

“I feel like all of that stuff was taken way out of proportion,” he said. “He can have some cheat meals, and he’s not crazy like that. But during the season, he’s obviously very dialed in, which you should be.”

Cole is gluten-free, dairy-free and watches his own diet, so he was never on MacKinnon’s culinary hit list while playing for the Avalanche. But he said the pressure from MacKinnon on his teammates to eat right was real.

“There were guys on our team where he did not pull any punches. He’s like, ‘You are fat. Stop eating s—,'” Cole said. “In his defense, he’s not wrong. He’s just so blunt and honest and doesn’t pull any punches. He’s like, ‘I’m not gonna give a s—. It’s true.’ And it is 99% of the time.”

MacKinnon is far from the only NHL player to place a high value on nutrition.

“He’s pretty strict. But I think nowadays, all the guys are so aware,” Pittsburgh Penguins star Sidney Crosby said. “I’d say we’re pretty close [in diet], though.”

Crosby and MacKinnon. Two NHL superstars from Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia. An idol who befriended a fan, and is now his offseason training partner.

“He and Sid are good buddies,” said Cole, who was also Crosby’s teammate with the Penguins, “and they’re both very similar in that sense — hyper, hyper competitive.”

CROSBY FIRST MET MacKinnon when Nate was 17, playing for the Halifax Mooseheads of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League. MacKinnon would go back to Cole Harbour in the summer and train there, as would Crosby.

The Penguins star and the Avalanche star spoke before the playoffs, but MacKinnon declined to share what they discussed. Crosby has said the two have had candid conversations about hockey, including the mental side of the game.

“I think it’s something he’s aware of and I think the big part of it is recognizing that. It’s always easy to sit there and say, you know, I wanna improve something. I think it’s just experience. He’ll go through different things than he has already that he’ll learn and figure out,” Crosby said. “You’re always learning. I’m still trying to figure it out and I’m sure he is too.”

Crosby has matured into an even-tempered leader after coming into the league as an enfant terrible. But MacKinnon warned against mistaking that serenity for a lack of aggression.

“I wouldn’t say he’s chill. He’s the most competitive guy I know. I think earlier in his career, he kinda wore his emotions on his sleeve. And now he’s calmer,” MacKinnon said of Crosby. “I think it’s better to be like that. I think every year I’m getting a little bit [calmer]. But I definitely don’t think I’ll be there anytime soon, for sure.”

While MacKinnon learned from Crosby’s demeanor, he also adopted Sid’s total immersion into hockey. Cole thinks MacKinnon started to breathe the sport in 2016-17, which was Jared Bednar’s first season as head coach and the nadir of the franchise, as the Avalanche finished last in the league with a .293 points percentage.

“They are both extremely hockey-centric,” Cole said. “That’s how Sid’s always been wired. But to be honest, for Nate it was a conscious decision he made after that really bad losing season they had.

“He felt he needed to live and breathe and do everything he could to be successful because that sucked,” Cole continued. “I think he made a conscious decision: ‘That was miserable. That was the worst season I’ve ever been a part of. I am never going to let that happen again. And I am going to hold myself accountable and hold everyone else accountable to make sure it never happens again.'”

MacKinnon’s approach to practices and teammates was amplified in the years between the last-place season and the team’s recent postseason failures. Just like Crosby learned to reel in his intensity, so has MacKinnon — to the Avalanche’s benefit.

“He’s always gonna push, he’s always going to be the driver of our offense and put a lot of responsibility on himself, but I feel like he’s let himself relax a little bit more,” Bednar said. “There’s a little bit more inner confidence in what he can accomplish over the years and what our team can accomplish if he plays his role to the best of his ability. It doesn’t have to be the perfect game every night.”

POST-PLAYOFF ELIMINATION press conferences have been a place where MacKinnon’s emotions are on full display. He would look devastated, despondent and utterly defeated.

Like after last postseason, when the Avalanche lost to the Vegas Golden Knights in six games and MacKinnon said this:

“For sure, there’s always next year. That’s all we talk about, I feel like. I mean, I’m going into my ninth year next year and I haven’t won s—.”

Looking back on that press conference, MacKinnon said that his team’s unwavering belief that it could finally be the year led to his sullen denouncement.

“You don’t have many opportunities. I mean, I’ve probably had, like, two or three, maybe, possibilities of winning in nine seasons. So whenever you feel like you’re that close to winning with the team you have and you don’t … you know, I think we’re all upset. So it wasn’t just me, it was all the guys,” he said.

MacKinnon says he’s not that guy anymore.

“I feel like a different person from that year. I was very emotional. You know, I’d be emotional again if we don’t win. But I think the mindset is a bit more even-keeled, a lot more positive,” he said. “Sometimes when you want it — and you try so, so hard — it doesn’t work out. The goal is to win.”

It’s somewhat simplistic, but the Colorado Avalanche are Stanley Cup champions now because they failed to become one for the last few seasons. They learned from losing in seven games to the San Jose Sharks in 2019; grew from that 2020 Game 7 overtime loss to the Dallas Stars; understood what went wrong in blowing a 2-0 series lead to the Golden Knights in 2021.

“Every time you lose, you have to learn a little bit and figure a few things out. Vegas kinda took it to us and we got away from how we play to our strengths. We got a little timid out there. We were a little hesitant, I think,” MacKinnon said. “When you play like that, you’re not gonna win against a team that is rolling.”

It’s a beautiful coincidence that the Avalanche finally captured the Stanley Cup against the Lightning, as the teams have similar paths to glory. Tampa Bay has talked openly about “learning how to win” through playoff disappointments. Their 2019 first-round playoff sweep at the hands of the Columbus Blue Jackets is a key moment in their origin story, showing the Lightning how they needed to play — and how they needed to think — to succeed in the postseason.

“Knowing how devastating that was for the group, it was pretty easy to get mad at each other, point fingers. But everyone looked in the mirror and came back the next year with a little bit of a chip on their shoulder,” Tampa Bay defenseman Zach Bogosian said of the Lightning.

Erik Johnson said the Avalanche took inspiration from the Lightning’s resilience.

“I think we knew what they had been through. They did lose to Columbus that one year in the playoffs and everyone sort of wrote them off. They went through some ups and downs, and now they’re the team everyone is trying to emulate,” Johnson said. “Mentally, we’ve come a long way from where we’ve been. Sometimes you have to learn from those losses and those defeats. To win, you have to go through some heartache sometimes. For us, it’s been about staying on the gas and not being content.”

Makar echoed that lesson: No matter what the situation is, the Avalanche have to remain vigilant.

Like, for example, eliminating an opponent after they’ve put them on the ropes.

“One of the things we’ve taken from last year is that when we’d get down in games, guys would get frustrated or start looking forward. Even if we won a game, we might take our foot off the gas,” he said. “But I feel like this team, we’re so set in trying to do our best and play our successful style.”

It wasn’t just the players that took a lesson from the Lightning. Incredible as it is to ponder now after back-to-back Stanley Cup wins, there was talk about whether the Tampa Bay core should have been blown up after a series of playoff disappointments.

“After 2019, I was a little skeptical, I’ll tell you that. But we kept the band together. We kept the faith,” Cooper said.

The Avalanche did the same despite four straight seasons without an appearance in the third round.

“It’s a belief. It’s a belief in your core,” GM Joe Sakic said. “You have to learn. You have to grow. Over time, we kept getting a little bit better. Especially this year, we really competed.”

MacKinnon was a leader in that regard, doing everything that was asked of him. He also learned that he didn’t have to win games all by himself.

“I think one of the areas where he’s grown this year is he hasn’t put so much … I feel like he’s more relaxed in our team game. I think there’s a confidence in our team game where he doesn’t put too much weight on his own shoulders,” Bednar said. “It doesn’t have to be a three- or four-point night. That’s where I see the growth from Nate. It’s just a more mature player every year that we’ve had him here, especially come playoff time with the experiences that we’ve gone through.”

All of it leading to the ultimate experience — winning the Stanley Cup together, with MacKinnon leading the way.